Alachua County Truth & Reconciliation | EJI Community Remembrance Project I 10.23.21 |

*

[I started writing this in Fall 2019 following the death of the Swiss photographer, Robert Frank. The connection? His most well-known book of images, The Americans, and specifically the image on the book’s cover – Trolley, New Orleans, 1955. As a photograph of time and place it is brilliant social commentary; read left to right – front of the trolley to back – was/is a 5-panel tableau of Supremacist-created and enforced racial hierarchy and social power in the U.S. And, that – and yeah – and in my head and right straight back and down that gravitational rabbit hole to growing up…]

Gainesville, FL is almost exactly half way between St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast and Cedar Key on the Gulf coast. The past isn’t dead, wrote one chronicler of the Deep South, it isn’t even past.

We moved to Alachua Co. in 1973. I was in first grade and for the first 4 years we lived in Gainesville I went to the mostly White elementary school on the west side of town. The school was across the street from the pasture with the horses that would soon become the Oaks Mall. In 1977- towards the end of that decade in which the desegregation of public schools was finally being forced by state law – our neighborhood was redrawn as one of the many to be bused over into a different part of town and a different school. In 1978, I started middle school and the process repeated itself: 6th grade in the mostly White middle school on the west side of town; 7th and 8th grade at the school not just across town, but up to the Archer Road and then that turn down that road deep-shaded with oaks and holding that low-slung church in that bend like the slowest of slow-moving rivers. Every day for two years our bus took that road and every day for two years I loved the arc of that curve and that quiet church.

At some point in middle school I saw that photograph: a young brown-skinned woman, perhaps not much older than a child, with an expression that read to me as fear and that White man in a pose as though he was traipsing lightheartedly along the edge of the pool with a milk jug in his hand. Tra la la went his pose. And he was pouring the contents of that jug into the pool. Where people were swimming. 1964. I may have seen that image first in 1979 – a 15 year gap that was an eternity, of course, to a 12 year old, but a reality that from this vantage in 2020 was the equivalent of 2005. Is the world substantively different now than it was 15 years ago? Maybe. Or no, not really. 15 years before I saw that image, a White man in St. Augustine was pouring acid into a pool in which brown-skinned people were swimming. The past isn’t even past. That photograph stopped me short that day. I’ve never forgotten it.

At some point in high school I put two fragments together that I’d been handed in class and history rattled down and dropped: Rosewood. There on the road to Cedar Key is the highway sign: Rosewood – the last small town before you hit the pines and causeway and the place we’d get oysters from on Christmas day. There is the sign. And there was no town. And no real conversation yet about local racial history at our high school, but we had a library and the librarian was interested in helping and we looked it up. 1923. Charges against a Black man by a White woman and the White community lost their sh*t. An unknown number of Black community members were killed and their cedar slab homes were burned to the ground.

What we read was that after days and nights of hiding, surviving community members made it out and away along the rail line. Some made it out on foot. Some were evacuated by train. This happened in a January, and the middle of winter in north Florida is plenty cold and folks who had escaped the violence had spent nights hiding in and amongst the trees and the dark water and, although it was winter and nothing would have been moving very fast, the snakes and the gators. And then here finally came the train – And would you trust it? Would you have even felt you had a choice in whether to climb on board? And I remember something like the vertigo of history falling open: 1923. And this was 1983, maybe. So, 60 years. An even larger gap that was an even greater eternity except for this: if you were 10 years old in 1923 – old enough to have a clear memory of that night and of that week of hiding – you could have still been alive in 1983. And the terror of that experience could have been the silent anchor of your entire world. And I walked back out into my high school day not even really understanding what that vertigo was, but it was this: The past isn’t dead. It is alive and it is experienced in human lifetimes. And there it went, blinking on large and loud and real, growing up a White kid dropped there into North Florida in the last quarter of the 20th century.

*

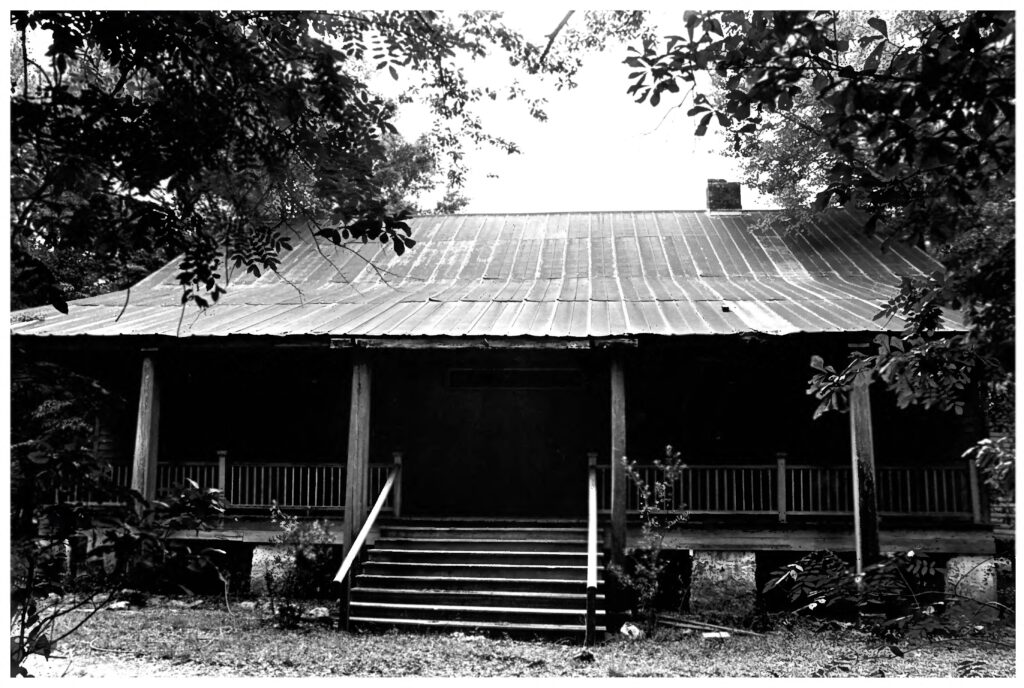

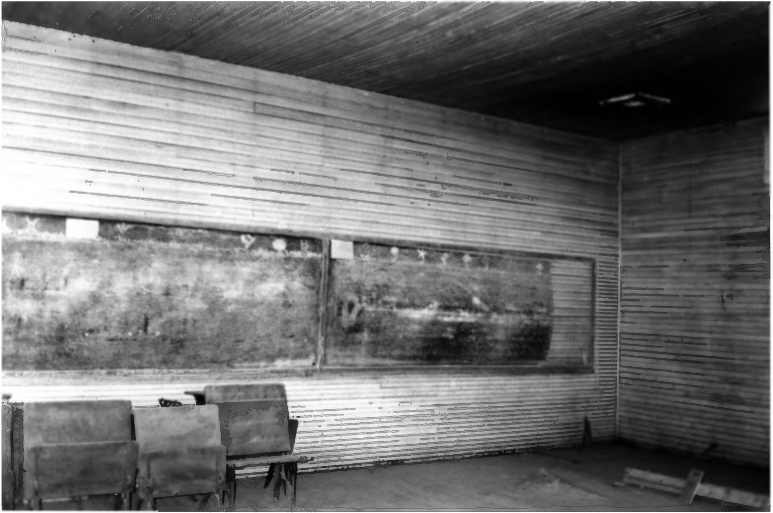

photographs: Haile Homestead (c.1985); LibertyHill SchoolHouse (c.2003); Gainesville, FL

[You could walk in from the Archer Road or you could cut in through the woods when that neighborhood they’d been building was still new. I don’t remember when I first knew it was there. They’d filmed a movie there while I was still in middle school and had cleaned things up a bit – I don’t think I knew at all about the movie at the time – but slowly the volume turns up on history, you know? And then you can’t remember when you didn’t used to hear it. It was pretty much like this when we found it for ourselves in high school. 1983? 1984? I have no idea still what to make of that memory. Laurel oaks and saw palmetto and that whitegray sand in the woods of north Florida. For a time after that, we’d walk back in through the woods and just…look at it. It never occurred to us to get close enough to walk up onto the porch or go inside.]

*

*

I can tell this only from the vantage that I know:

A single line is just that thing: a line: I am White

Two lines that cross pin down a point within a space: I grew up in the South

Three lines that cross are a fix: three lines is the minimum you need to be able to trust what you know about where you are.

I am in Gainesville and I am here for one reason: to bury the ashes of my father’s body.

I am in Gainesville and I am here for two reasons: in the woods behind where my mother now lives alone is a single room Black schoolhouse that had neither lights nor water until it closed in 1952. That year matters for the legal case and the momentum that swung slow into motion – but then they all matter: sit quiet with time and the weight always gets heavy.

I am in Gainesville and when the third line crosses, history pours through the opening: between the end of the Civil War and the middle of the 1920s, 46 Black men and women were murdered by lynching in this county in which I grew up. I am in Gainesville for the third line crossing: I am here to pay my respects. Three lines crossing is a fix: I walked into the woods today through the liana and leaned my back against the holy as the rain came down. We placed the ashes of my father’s body in a box and placed that box in the ground and my brothers shoveled in the earth. I pressed my hands against his memory and then we stood underneath the oak trees and opened to the silence as the rain came down. Three lines crossing is a fix. What is it that I know? That what he’d told me once about the thinness of that veil is true, and that sanity – in the South and as history overflows – is a fragile, fragile thing.

***

Why? she asked. This is why. Because I know where this is. My father’s parents moved to FL a few years before we did. My grandfather had retired from Otis Elevator and he and Nana left Buffalo with the kitchen door swinging. They bought a 2-bedroom house in Dunedin on a tidy little street with a perfectly green lawn and shiny-leaved grapefruit and orange trees in the front and back yards. We would walk to the railroad tracks and leave pennies on the rails for the trains to flatten and then sit at the table on the back patio and eat creamy peanut butter on Ritz crackers and KoolWhip from the tub on (noideawhatthatflavorwas) red jello. Grandpa would take us fishing from the pier and right here, right now, I can feel the tug on the line with the rod bending in both hands. Every visit we went to the library and I spent hours over those summers reading books. We would go to Morrison’s Cafeteria for dinners out and when you went through the cafeteria line the first items were the pies – wedges of chocolate pudding or key lime or lemon with the meringue on top. Nana and Grandpa would take us to the beach and we’d get soft-serve ice cream in vanilla, chocolate or swirl. When Grandpa took us to get ice cream, we could get it dipped in chocolate because he liked that too. The beach was always Clearwater Beach. Drive from Dunedin through Clearwater, past the Church of Scientology tower there downtown and out across the causeway. I read the first article about this cemetery and found it on a map. Jesus. Do you see? Nostalgia weighs nothing compared to history; if you don’t tether nostalgia, it floats away; if you do tether it, it slowly wrecks your compass and leaves you drifting aimless. What is it that I know? I know that if you’re White you get to choose, so, which would you rather have: a balloon filled with helium or a Brunton in your pocket?

*